Anarchists are part of the global conversation on what’s broken in the world, but when things really fall apart—like with the current Ebola outbreak—is the state the only answer? How might a stateless society respond to a challenge like this one? This article provides an anarchist response to these questions, while highlighting issues that require those of us with anarchist politics to carefully think through our position.

This is part two of a two part series. Part one is available here: Part one: What Went Wrong?

Key points:

- Just as with the AIDS epidemic, grassroots movements can and should pressure state and corporate institutions to save lives today, while staying critical and building independent alternatives.

- A future stateless society can and must maintain systems to support human health. These systems are generally more complex than other systems anarchists have maintained during moments of revolt, but doing so is feasible.

- Too many anarchists offer critique and deconstruction under the banner of anarchism, but don’t speak as anarchists when they put forward large-scale alternatives. This has contributed to the idea that anarchist solutions are only local, low-tech, and limited.

- On the other hand, health care systems, scientific research, and community systems of care reflect anarchist traditions of mutual aid, free association, and care for all people regardless of status or class.

- Global recognition that #BlackLivesMatter means fighting back not just when Black lives are senselessly taken, but when insufficient value and material care are put forward to sustain them.

An Anarchist Response to Ebola: Visions and Questions | Part Two: Envisioning an Anarchist Alternative

by Carwil Bjork-James with Chuck Munson

Clearly the current epidemic is being made more severe by incompetent governments, agencies, public health organizations, international air travel, and people just reacting to it as frightened humans. As we have seen in other crises, the state has failed to adequately prepare for or serve the people most in need, a situation that is reminiscent of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy in the United States. After these disasters, activists-turned-recovery-agents created decentralized, horizontally organized response efforts. These efforts, limited as they are, make it possible to ask a larger question: If we lived in an anarchist society where there was no state, would it be possible to deal with a public health crisis?

Vision Question 1: Even if global anarchist revolution happened tomorrow, there would still be many decades of rebuilding and redistributing to undo the concentration of wealth and the racialization and continental distribution of poverty. These are the consequences of their property becoming our theft. How do we propose to concretely reverse imbalances like that in the number of trained medical professionals, which made this Ebola outbreak possible?

Vision Question 1: Even if global anarchist revolution happened tomorrow, there would still be many decades of rebuilding and redistributing to undo the concentration of wealth and the racialization and continental distribution of poverty. These are the consequences of their property becoming our theft. How do we propose to concretely reverse imbalances like that in the number of trained medical professionals, which made this Ebola outbreak possible?

Vision Question 2: How do anarchists balance between celebrating the potential for volunteer, and horizontally organized responses to crises like the current Ebola outbreak and disruptively pressuring the state, capitalist, and vertical institutions that currently control much of the needed resources to do what they can? Or should anarchists maintain a partisan silence about the latter question?

What does confronting the Ebola outbreak mean?

The existing tools for dealing with Ebola, in the absence of a vaccine or more specialized treatment, are straightforward. Outside of careful protocols, Ebola is a particularly cruel disease, striking hardest at those who directly care for the sick, whether families, generous strangers, or dedicated health workers. With careful adherence to protective regimens, Ebola patients can often be sustained through the disease, with much less additional spreading of the disease. But these routines are built on the ready supply of “staff, stuff, space, and systems”—the material, human, and physical components of health care provision. Health workers need materials to protect themselves and their patients, clean and well-stocked facilities to work in, and adequate replacements when they need rest or treatment. Treating Ebola only makes sense within a public service that is an ongoing part of society.

Like HIV/AIDS during the initial years of the pandemic, Ebola is a disease which is striking first and hardest at the lives of people who have been devalued by the global power structure. Like HIV/AIDS, it threatens the future of whole communities, even countries, while posing a less direct threat to the global public at large.

Three dangerous responses that played out with HIV/AIDS are relevant for how we confront Ebola. (The difference is that the Ebola virus disease can shift from a local to a global threat much faster.) First, that the disease has become an excuse for further stigmatizing members of large groups of people; we are already seeing disturbing overreactions associating Africans, West Africans, or Black people with Ebola. Second, the international community failed to prioritize responding to a disease until it affected high-status people. This response to an infectious disease leads to unnecessary deaths and greater ultimate costs. Third, new and existing solutions are only accessible at a high price, out of reach of much of the world. A vital struggle looms over who gets access to newly created treatments and prevention measures as these are rolled out for Ebola. Those with wealth and exaggerated fears must not be allowed to outbid those who are at greatest risk.

Fortunately, the response to the AIDS pandemic also taught some key lessons for today’s crisis. AIDS patient-activists fought to have a seat at the planning table alongside doctors and pharmacologists. They also built community-centered health clinics, disrupted political life to win funding for treatment, changed the process of rolling out drugs in favor of dying patients, defied global intellectual property law to make drugs available to the global south, and fought back against stigmatizing the disease and the people most vulnerable to it.

Vision Question 3: There have been many excellent grassroots public health efforts, from ACT UP to the Common Ground clinic after Hurricane Katrina, but they have suffered from limitations of infrastructure once they get beyond a certain scale. What organizing mechanisms can we put in place to make such efforts function at the scale of the problems they confront? What can we learn from non-horizontal institutions like Cuba’s health service or from the formalized funding that powers Doctors Without Borders? If the scale of liberatory institutions is limited, how do we instill a capacity to multiply such institutions rapidly in response to urgent needs? How might we fund science, including medical research, and mass public services outside the current profit-driven system?

Vision Question 3: There have been many excellent grassroots public health efforts, from ACT UP to the Common Ground clinic after Hurricane Katrina, but they have suffered from limitations of infrastructure once they get beyond a certain scale. What organizing mechanisms can we put in place to make such efforts function at the scale of the problems they confront? What can we learn from non-horizontal institutions like Cuba’s health service or from the formalized funding that powers Doctors Without Borders? If the scale of liberatory institutions is limited, how do we instill a capacity to multiply such institutions rapidly in response to urgent needs? How might we fund science, including medical research, and mass public services outside the current profit-driven system?

Public health and epidemiology: Public goods? State surveillance? Both?

We know about Ebola and how to treat it because of a chain of researchers and a larger framework of virology, medicine, and epidemiology that have traced the virus’s incursions into human communities. Their work has taken us from nearly incomprehensible tragedy in 1976 to the ability to conceptualize and plan the urgent choices needed to bring to a halt a far larger epidemic today.

Such scientific systems are among the largest decentralized efforts humans have ever created. The scientific method operates through both collective memory and collective skepticism towards any permanently designated authority. At the same time, a permanently maintained collective memory of scientific facts is vital to the enterprise. So too is the continuous interchange of knowledge, training of researchers, health care workers, and public health specialists. Approaches to understanding disease, learning how microbes respond to possible treatments, and monitoring the spread and decline of waves of infection are all accomplished through these decentralized mechanisms. They also all rely on permanent public systems.

However, the anti-authoritarian story of science, while embraced by many scientists, leaves out the ways that many scientific ways of looking at the world are intertwined with those of the state. Indeed many branches of science emerge out of the modern state’s urgent desire to monitor, enumerate, and plan the future of its subjects—hence the word statistics, from science of state. Epidemiology depends on counting disease among locatable, traceable, identifiable patients in a landscape where everyone is visible. If one thinks of modern governance as the hardware and operating system through which one is “watched, inspected, spied upon, directed, law-driven, numbered, regulated, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, checked, estimated, valued, censured, commanded … noted, registered, counted, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorized, admonished, prevented, forbidden, reformed, corrected, punished” (in the words of Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin), then epidemiology is one of the “killer apps” that run on that operating system. Or rather, the opposite of killer. So, public health as a concept is inseparable from some of this apparatus of monitoring and responding.

Vision Question 4: Is anarchism about destroying not just the centralized state but the hardware and the operating system it has built to (over)see its citizens? About separating it from the control of any one entity? About fragmenting control into smaller pieces? About eliminating some but not all of these possible operations? About maintaining surveillance on microbes, for instance, while evading/anonymizing surveillance on individuals?

We imagine an anarchist society as one that is decentralized and which views the amassing of power and control as a risk that needs to be countered through the design of its institutions and in the culture of working together. To prevent the dangerous intersection of surveillance and public health, community-level clinics could choose to minimize the exposure of their patients. They could encrypt and anonymize health details before sharing them outside the local community, something that is much more unlikely in state and capitalist health systems. An anarchist society would also be one without any single organization or institution in control of the rest. Unlike the world we live in now, no one organization (even a workplace taking on an important task) would have the universal ability to inspect all records, much less the ability to back up such a demand with force. Instead, when a priority arises, the collective best prepared to address it would approach others for their cooperation.

Surprisingly, the situation with Ebola now foreshadows some of such a process. Truly effective response to Ebola requires community involvement and active participation in prevention education, treatment, and alterations to daily routines of life. None of the regional states are really strong enough to force that kind of compliance upon outlying rural communities or dense urban neighborhoods. As with many day-to-day necessities, consent and persuasion are the channels through which things actually get done. Anarchists strive to generalize that principle as much as is humanly possible.

How would a society without a state respond to Ebola?

A classic question about anarchism is “Who cleans up the trash in an anarchist society?” In contrast to capitalist society, where the answer is someone who needs the money more than they dislike the job, anarchists generally talk about either the absolute need to take responsibility locally, the possibility of rewarding people for doing undesirable tasks, or the creation of a rotational system where everyone has to do some of the hard, undesirable, or dangerous work. “Nobody wants to, so everybody has to,” can become a society-wide slogan, perhaps with a system of mutual confirmation, making sure things get done.

Public health, though, is a little more complex. First, public health systems are complex and interdependent. Doctors and nurses rely on fully stocked supply rooms, sterilized equipment, and carefully tested medicines. So, we’re talking about multiple workplaces, coordinating together. On the model of worker-run cooperatives around the world and telephone and transportation systems during workers’ uprisings across history, we envision people maintaining careful collaboration among themselves. Indeed, we suspect that excessive hierarchy, the profit motive, competition among private firms, and billing paperwork often get in the way of meaningful coordination.

In terms of recruiting people to step forward and treat a threatening illness, the current crisis shows that motivation is not the problem. Whether through independent initiatives like Doctors Without Borders, state-run cooperation agencies like Cuba’s, or recruitment efforts like that recently carried out by Avaaz, a volunteer-based system is adequate to staff response during moments. Given the opportunity, many, many people are willing to take risks, do repetitive tasks, and apply the skills they have to common problems. Rather, the challenge is to make sure that needed skills are widely taught, that systems for healing people are kept in place, and that supplies are made to flow smoothly to where they are most needed.

Still, the effort to treat people with infectious diseases, take the necessary precautions to prevent infection, or administer immunizations to an entire population requires both detailed, onerous work and careful monitoring of populations at large. One face of a health system is the collective workplace of healers and caretakers, but another is factories that produce basic supplies and adequately cleaned rooms, and still another is a monitoring system that records the health of both patients and the public. How do we take these less glamourous and more factory-like and state-like roles seriously? If we envision a less factory-like and less state-like society, how do we maintain enough of these ways of working to maintain life-sustaining systems like health care for all?

An ongoing continuous effort to provide health support locally is the most vital, and most missing, ingredient in the region (and this explains why and how MSF has been able to step forward so decisively). Relief organizations like MSF, community- and neighborhood-level clinics, public health systems, and the scientific community are all examples of the type institutions we need to maintain. Likewise, most coordination among them is done a way that is voluntary, and based on mutual agreement rather than coercion and commands.

Dealing with an Ebola outbreak does mean taking some actions extremely quickly. Rapid mobilization of doctors, building of treatment centers, or supplying of sterile equipment this month is the equivalent of several times that effort next month. The current crisis demonstrates that no existing social system does this kind of acceleration very effectively.

Massive spare capacity to act logistically, and to supply medical personnel (currently expressed through the US military’s capacity to build infrastructure, and the Cuban medical systems capacity to send doctors to any place on Earth) are other prerequisites for action. We envision a cooperatively-run economy to be capable of diverting these capacities from other uses more flexibly than either a capitalist or state-socialist order: if work is self-organized then any collective of workers might deploy to assist in a crisis, not just those that are part of the state or a purpose-built NGO. Imagine workers at FedEx being able to choose to dedicate some of their planes for sending vital supplies, or a builder’s union in Nigeria erecting a dozen Ebola treatment centers. If profit were not the constant purpose of most labor, what other human priorities might be put to the fore? What compromises or hardships would individuals and communities willingly choose in service of helping others? Outside of crisis, how might the gross disparities in resources, preparedness, and necessary tools for caring for human lives be undone, erasing the vulnerability created by centuries of extracting wealth from Africa?

Vision Question 5: We know that capitalism overproduces private goods and services (for the wealthy) and underproduces goods and services that can be enjoyed by all. Yet despite some efforts to reclaim common spaces or provide free goods/services, there is a void in analysis by contemporary anarchists in the USA about redistributing social effort towards the collective needs or desires. How do we start talking about that kind of public goods anarchism?

Vision Question 6: What model of public organizations do anarchists see as becoming more commonplace in an anarchist social order? A vast, networked MSF? Expanded or reduced institutions like the CDC and the WHO? A National Health Service in every country, or in no country?

Vision Question 7: Are quarantines compatible with anarchist ideas about freedom from coercion? In a society without a state, who should consider themselves empowered to coerce someone else to save lives, and under what conditions?

In closing, the Ebola outbreak is a difficult problem, but a solvable one. The current outbreak thrives on conditions created by colonialism, capitalism, and war. Late in the day, governments and wealthy individuals have put themselves forward as the solution to this crisis, even though much of the hard work is being done by local community members and independently-funded, modestly compensated volunteers.

People curious or skeptical about anarchism are right to ask how a stateless society would handle a challenge like this one better than the current world order is. Those of us who envision a society that works differently ought to have serious answers to their questions. This article is meant to both sketch out that answer and prompt discussion among those striving for a radical transformation of society, asking what we need to re-think or clear up about our politics to engage seriously with issues like this.

Ebola is far from the most difficult problem we will face in our lifetimes. We anarchists are part of the world community that confronts such problems here and now. Our zeal to make the world just and free must lead not just to imagining an ideal society, but fighting for necessary care and wisdom in collective decisions today. We need to ask ourselves how to fight for the lives that are at risk when these decisions are made by institutions we rightly distrust.

Part one is available here: Part one: What Went Wrong?

Carwil Bjork-James has collaborated in directly democratic organizations including the Independent Media Center, Direct Action to Stop the War, and Free University of New York City. He lives in Tennessee and is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Vanderbilt University.

Chuck Munson is the coordinator and editor for Infoshop News, an online news service which celebrates its 20th anniversary in January 2015. He has also written for Alternative Press Review, Practical Anarchy, and other magazines. He was also a webmaster for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and Science magazine.

Further Reading

Ebola: Capitalism’s War Against Humanity, Anarchist Federation

Ebola: Five ways the CDC got it wrong, CNN

Aids: Origin of pandemic ‘was 1920s Kinshasa’, BBC

Special Collection: The Ebola Epidemic, Science

Ebola Is Coming. A Travel Ban Won’t Stop Outbreaks, Forbes

One Simple Chart Shows How We Can Stop Ebola From Taking Any More Lives, Business Insider

Dr. Atul Gawande: Ebola is “Eminently Stoppable,” But Global Response Has Been “Pathetic”, Democracy Now!

‘Assassination’ of Public Health Systems Driving Ebola Crisis, Experts Warn, Common Dreams

Obama Has Been Fighting Doctors Without Borders For Years, Huffington Post

Oil palm explosion driving West Africa’s Ebola outbreak, The Ecologist

Ebola Vaccine, Ready for Test, Sat on the Shelf, The New York Times

Every Single Flu Vaccine Myth, Debunked, i09

A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement, Feminist Wire

A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit, Penguin Books, 2009.

Free Radicals: The Secret Anarchy of Science, Michael Brooks. Overlook Hardcover, 2012

Images:

Occupy Sandy: A leaderless grassroots relief and organizing effort that responded to Hurricane Sandy in the New York metropolitan area. (two photos cc-by-nc Not An Alternative)

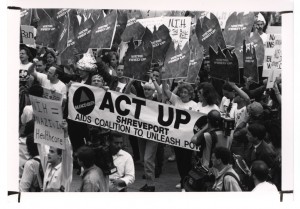

ACT UP activists storm the National Institutes of Health, part of a series of campaigns that changed the priorities of public health policy and the role of patients in confronting their illness. (photo cc-by-nc-sa NIH Library)

An Anarchist Response to Ebola | Part Two: Envisioning an Anarchist Alternative

Anarchists are part of the global conversation on what’s broken in the world, but when things really fall apart—like with the current Ebola outbreak—is the state the only answer? How might a stateless society respond to a challenge like this one? This article provides an anarchist response to these questions, while highlighting issues that require those of us with anarchist politics to carefully think through our position.

This is part two of a two part series. Part one is available here: Part one: What Went Wrong?

Key points:

An Anarchist Response to Ebola: Visions and Questions | Part Two: Envisioning an Anarchist Alternative

by Carwil Bjork-James with Chuck Munson

Clearly the current epidemic is being made more severe by incompetent governments, agencies, public health organizations, international air travel, and people just reacting to it as frightened humans. As we have seen in other crises, the state has failed to adequately prepare for or serve the people most in need, a situation that is reminiscent of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy in the United States. After these disasters, activists-turned-recovery-agents created decentralized, horizontally organized response efforts. These efforts, limited as they are, make it possible to ask a larger question: If we lived in an anarchist society where there was no state, would it be possible to deal with a public health crisis?

Vision Question 2: How do anarchists balance between celebrating the potential for volunteer, and horizontally organized responses to crises like the current Ebola outbreak and disruptively pressuring the state, capitalist, and vertical institutions that currently control much of the needed resources to do what they can? Or should anarchists maintain a partisan silence about the latter question?

What does confronting the Ebola outbreak mean?

The existing tools for dealing with Ebola, in the absence of a vaccine or more specialized treatment, are straightforward. Outside of careful protocols, Ebola is a particularly cruel disease, striking hardest at those who directly care for the sick, whether families, generous strangers, or dedicated health workers. With careful adherence to protective regimens, Ebola patients can often be sustained through the disease, with much less additional spreading of the disease. But these routines are built on the ready supply of “staff, stuff, space, and systems”—the material, human, and physical components of health care provision. Health workers need materials to protect themselves and their patients, clean and well-stocked facilities to work in, and adequate replacements when they need rest or treatment. Treating Ebola only makes sense within a public service that is an ongoing part of society.

Like HIV/AIDS during the initial years of the pandemic, Ebola is a disease which is striking first and hardest at the lives of people who have been devalued by the global power structure. Like HIV/AIDS, it threatens the future of whole communities, even countries, while posing a less direct threat to the global public at large.

Three dangerous responses that played out with HIV/AIDS are relevant for how we confront Ebola. (The difference is that the Ebola virus disease can shift from a local to a global threat much faster.) First, that the disease has become an excuse for further stigmatizing members of large groups of people; we are already seeing disturbing overreactions associating Africans, West Africans, or Black people with Ebola. Second, the international community failed to prioritize responding to a disease until it affected high-status people. This response to an infectious disease leads to unnecessary deaths and greater ultimate costs. Third, new and existing solutions are only accessible at a high price, out of reach of much of the world. A vital struggle looms over who gets access to newly created treatments and prevention measures as these are rolled out for Ebola. Those with wealth and exaggerated fears must not be allowed to outbid those who are at greatest risk.

Fortunately, the response to the AIDS pandemic also taught some key lessons for today’s crisis. AIDS patient-activists fought to have a seat at the planning table alongside doctors and pharmacologists. They also built community-centered health clinics, disrupted political life to win funding for treatment, changed the process of rolling out drugs in favor of dying patients, defied global intellectual property law to make drugs available to the global south, and fought back against stigmatizing the disease and the people most vulnerable to it.

Public health and epidemiology: Public goods? State surveillance? Both?

We know about Ebola and how to treat it because of a chain of researchers and a larger framework of virology, medicine, and epidemiology that have traced the virus’s incursions into human communities. Their work has taken us from nearly incomprehensible tragedy in 1976 to the ability to conceptualize and plan the urgent choices needed to bring to a halt a far larger epidemic today.

Such scientific systems are among the largest decentralized efforts humans have ever created. The scientific method operates through both collective memory and collective skepticism towards any permanently designated authority. At the same time, a permanently maintained collective memory of scientific facts is vital to the enterprise. So too is the continuous interchange of knowledge, training of researchers, health care workers, and public health specialists. Approaches to understanding disease, learning how microbes respond to possible treatments, and monitoring the spread and decline of waves of infection are all accomplished through these decentralized mechanisms. They also all rely on permanent public systems.

However, the anti-authoritarian story of science, while embraced by many scientists, leaves out the ways that many scientific ways of looking at the world are intertwined with those of the state. Indeed many branches of science emerge out of the modern state’s urgent desire to monitor, enumerate, and plan the future of its subjects—hence the word statistics, from science of state. Epidemiology depends on counting disease among locatable, traceable, identifiable patients in a landscape where everyone is visible. If one thinks of modern governance as the hardware and operating system through which one is “watched, inspected, spied upon, directed, law-driven, numbered, regulated, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, checked, estimated, valued, censured, commanded … noted, registered, counted, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorized, admonished, prevented, forbidden, reformed, corrected, punished” (in the words of Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin), then epidemiology is one of the “killer apps” that run on that operating system. Or rather, the opposite of killer. So, public health as a concept is inseparable from some of this apparatus of monitoring and responding.

Vision Question 4: Is anarchism about destroying not just the centralized state but the hardware and the operating system it has built to (over)see its citizens? About separating it from the control of any one entity? About fragmenting control into smaller pieces? About eliminating some but not all of these possible operations? About maintaining surveillance on microbes, for instance, while evading/anonymizing surveillance on individuals?

We imagine an anarchist society as one that is decentralized and which views the amassing of power and control as a risk that needs to be countered through the design of its institutions and in the culture of working together. To prevent the dangerous intersection of surveillance and public health, community-level clinics could choose to minimize the exposure of their patients. They could encrypt and anonymize health details before sharing them outside the local community, something that is much more unlikely in state and capitalist health systems. An anarchist society would also be one without any single organization or institution in control of the rest. Unlike the world we live in now, no one organization (even a workplace taking on an important task) would have the universal ability to inspect all records, much less the ability to back up such a demand with force. Instead, when a priority arises, the collective best prepared to address it would approach others for their cooperation.

Surprisingly, the situation with Ebola now foreshadows some of such a process. Truly effective response to Ebola requires community involvement and active participation in prevention education, treatment, and alterations to daily routines of life. None of the regional states are really strong enough to force that kind of compliance upon outlying rural communities or dense urban neighborhoods. As with many day-to-day necessities, consent and persuasion are the channels through which things actually get done. Anarchists strive to generalize that principle as much as is humanly possible.

How would a society without a state respond to Ebola?

A classic question about anarchism is “Who cleans up the trash in an anarchist society?” In contrast to capitalist society, where the answer is someone who needs the money more than they dislike the job, anarchists generally talk about either the absolute need to take responsibility locally, the possibility of rewarding people for doing undesirable tasks, or the creation of a rotational system where everyone has to do some of the hard, undesirable, or dangerous work. “Nobody wants to, so everybody has to,” can become a society-wide slogan, perhaps with a system of mutual confirmation, making sure things get done.

Public health, though, is a little more complex. First, public health systems are complex and interdependent. Doctors and nurses rely on fully stocked supply rooms, sterilized equipment, and carefully tested medicines. So, we’re talking about multiple workplaces, coordinating together. On the model of worker-run cooperatives around the world and telephone and transportation systems during workers’ uprisings across history, we envision people maintaining careful collaboration among themselves. Indeed, we suspect that excessive hierarchy, the profit motive, competition among private firms, and billing paperwork often get in the way of meaningful coordination.

In terms of recruiting people to step forward and treat a threatening illness, the current crisis shows that motivation is not the problem. Whether through independent initiatives like Doctors Without Borders, state-run cooperation agencies like Cuba’s, or recruitment efforts like that recently carried out by Avaaz, a volunteer-based system is adequate to staff response during moments. Given the opportunity, many, many people are willing to take risks, do repetitive tasks, and apply the skills they have to common problems. Rather, the challenge is to make sure that needed skills are widely taught, that systems for healing people are kept in place, and that supplies are made to flow smoothly to where they are most needed.

Still, the effort to treat people with infectious diseases, take the necessary precautions to prevent infection, or administer immunizations to an entire population requires both detailed, onerous work and careful monitoring of populations at large. One face of a health system is the collective workplace of healers and caretakers, but another is factories that produce basic supplies and adequately cleaned rooms, and still another is a monitoring system that records the health of both patients and the public. How do we take these less glamourous and more factory-like and state-like roles seriously? If we envision a less factory-like and less state-like society, how do we maintain enough of these ways of working to maintain life-sustaining systems like health care for all?

An ongoing continuous effort to provide health support locally is the most vital, and most missing, ingredient in the region (and this explains why and how MSF has been able to step forward so decisively). Relief organizations like MSF, community- and neighborhood-level clinics, public health systems, and the scientific community are all examples of the type institutions we need to maintain. Likewise, most coordination among them is done a way that is voluntary, and based on mutual agreement rather than coercion and commands.

Dealing with an Ebola outbreak does mean taking some actions extremely quickly. Rapid mobilization of doctors, building of treatment centers, or supplying of sterile equipment this month is the equivalent of several times that effort next month. The current crisis demonstrates that no existing social system does this kind of acceleration very effectively.

Massive spare capacity to act logistically, and to supply medical personnel (currently expressed through the US military’s capacity to build infrastructure, and the Cuban medical systems capacity to send doctors to any place on Earth) are other prerequisites for action. We envision a cooperatively-run economy to be capable of diverting these capacities from other uses more flexibly than either a capitalist or state-socialist order: if work is self-organized then any collective of workers might deploy to assist in a crisis, not just those that are part of the state or a purpose-built NGO. Imagine workers at FedEx being able to choose to dedicate some of their planes for sending vital supplies, or a builder’s union in Nigeria erecting a dozen Ebola treatment centers. If profit were not the constant purpose of most labor, what other human priorities might be put to the fore? What compromises or hardships would individuals and communities willingly choose in service of helping others? Outside of crisis, how might the gross disparities in resources, preparedness, and necessary tools for caring for human lives be undone, erasing the vulnerability created by centuries of extracting wealth from Africa?

Vision Question 5: We know that capitalism overproduces private goods and services (for the wealthy) and underproduces goods and services that can be enjoyed by all. Yet despite some efforts to reclaim common spaces or provide free goods/services, there is a void in analysis by contemporary anarchists in the USA about redistributing social effort towards the collective needs or desires. How do we start talking about that kind of public goods anarchism?

Vision Question 6: What model of public organizations do anarchists see as becoming more commonplace in an anarchist social order? A vast, networked MSF? Expanded or reduced institutions like the CDC and the WHO? A National Health Service in every country, or in no country?

Vision Question 7: Are quarantines compatible with anarchist ideas about freedom from coercion? In a society without a state, who should consider themselves empowered to coerce someone else to save lives, and under what conditions?

In closing, the Ebola outbreak is a difficult problem, but a solvable one. The current outbreak thrives on conditions created by colonialism, capitalism, and war. Late in the day, governments and wealthy individuals have put themselves forward as the solution to this crisis, even though much of the hard work is being done by local community members and independently-funded, modestly compensated volunteers.

People curious or skeptical about anarchism are right to ask how a stateless society would handle a challenge like this one better than the current world order is. Those of us who envision a society that works differently ought to have serious answers to their questions. This article is meant to both sketch out that answer and prompt discussion among those striving for a radical transformation of society, asking what we need to re-think or clear up about our politics to engage seriously with issues like this.

Ebola is far from the most difficult problem we will face in our lifetimes. We anarchists are part of the world community that confronts such problems here and now. Our zeal to make the world just and free must lead not just to imagining an ideal society, but fighting for necessary care and wisdom in collective decisions today. We need to ask ourselves how to fight for the lives that are at risk when these decisions are made by institutions we rightly distrust.

Part one is available here: Part one: What Went Wrong?

Carwil Bjork-James has collaborated in directly democratic organizations including the Independent Media Center, Direct Action to Stop the War, and Free University of New York City. He lives in Tennessee and is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Vanderbilt University.

Chuck Munson is the coordinator and editor for Infoshop News, an online news service which celebrates its 20th anniversary in January 2015. He has also written for Alternative Press Review, Practical Anarchy, and other magazines. He was also a webmaster for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and Science magazine.

Further Reading

Ebola: Capitalism’s War Against Humanity, Anarchist Federation

Ebola: Five ways the CDC got it wrong, CNN

Aids: Origin of pandemic ‘was 1920s Kinshasa’, BBC

Special Collection: The Ebola Epidemic, Science

Ebola Is Coming. A Travel Ban Won’t Stop Outbreaks, Forbes

One Simple Chart Shows How We Can Stop Ebola From Taking Any More Lives, Business Insider

Dr. Atul Gawande: Ebola is “Eminently Stoppable,” But Global Response Has Been “Pathetic”, Democracy Now!

‘Assassination’ of Public Health Systems Driving Ebola Crisis, Experts Warn, Common Dreams

Obama Has Been Fighting Doctors Without Borders For Years, Huffington Post

Oil palm explosion driving West Africa’s Ebola outbreak, The Ecologist

Ebola Vaccine, Ready for Test, Sat on the Shelf, The New York Times

Every Single Flu Vaccine Myth, Debunked, i09

A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement, Feminist Wire

A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit, Penguin Books, 2009.

Free Radicals: The Secret Anarchy of Science, Michael Brooks. Overlook Hardcover, 2012

Images:

Occupy Sandy: A leaderless grassroots relief and organizing effort that responded to Hurricane Sandy in the New York metropolitan area. (two photos cc-by-nc Not An Alternative)

ACT UP activists storm the National Institutes of Health, part of a series of campaigns that changed the priorities of public health policy and the role of patients in confronting their illness. (photo cc-by-nc-sa NIH Library)

Author

Chuck Munson is the coordinator and editor for Infoshop News, an online news service which celebrates its 20th anniversary in January 2015. He has also written for Alternative Press Review, Practical Anarchy, and other magazines. He was also a webmaster for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and Science magazine.

View all posts